"At the end of my suffering/there was a door"

Remembering Louise Glück

Yesterday—Friday the 13th of October—my phone started to buzz: the poet Louise Glück had died. My poet friends began to text each other to express our shock and our sadness over this unexpected news.

For so many poets of my generation, Louise Glück was a titan, one of the great American voices whose work was essential. As a young poet, I remember encountering her famous poem “Mock Orange” in a class taught by Lucie Brock-Broido, and I remember feeling a kind of giddiness at the revelation that one could express this kind of abjectness in a poem. Glück taught us that we didn’t need to be liked, to be good, to be approachable or universal. Her poems aren’t occasions for self-regard; they are far too lacerating and honest for that.

In 1992, I moved to New York City from Wisconsin, and through great luck and a certain amount of misplaced confidence, I had landed a job at The Academy of American Poets. My title, as I recall, was “Administrative Assistant,” which meant I was the office dogsbody. I ran errands all over New York, spent hours folding press releases and stuffing envelopes for mailings, being generally cheerful and helpful. It was also my job to attend and assist at the organization’s public events, which included the Academy’s weekly reading series. The Academy’s reading series was then one of the big poetry series in the country, and they were held at several venues around New York, including at the Alliance Française on East 60th Street, which is where I first saw Louise Glück and heard her read.

She had just finished writing The Wild Iris, and that night she read entirely from that book. I stood in the back of the small windowless auditorium, and she began to describe the book with a combination of determination and self-deprecation; yes, flowers were speaking, and so was God. Yes it all takes place in a garden and it is a kind of allegory. The book had been written in the course of a couple months, and had been born from her experience as a gardener at her home in Vermont. I remember her voice—flat, a bit nasal—and then the ways in which those poems changed the atmosphere of the room, and how they also changed me.

The recording I have linked to above is from that reading in 1992 (that’s me holding my breath in the back of the room). From that point on, I knew I was going to be devoted to her work. In years to come, I would get to know her a little, driving her around Palo Alto, California and squiring her around the Stanford campus when she came to visit. Years after that in 2014, we would read together in Woodstock, Vermont in an unadorned New England church which seemed to match the austerity of her poems as she read from Faithful and Virtuous Night which had just come out.

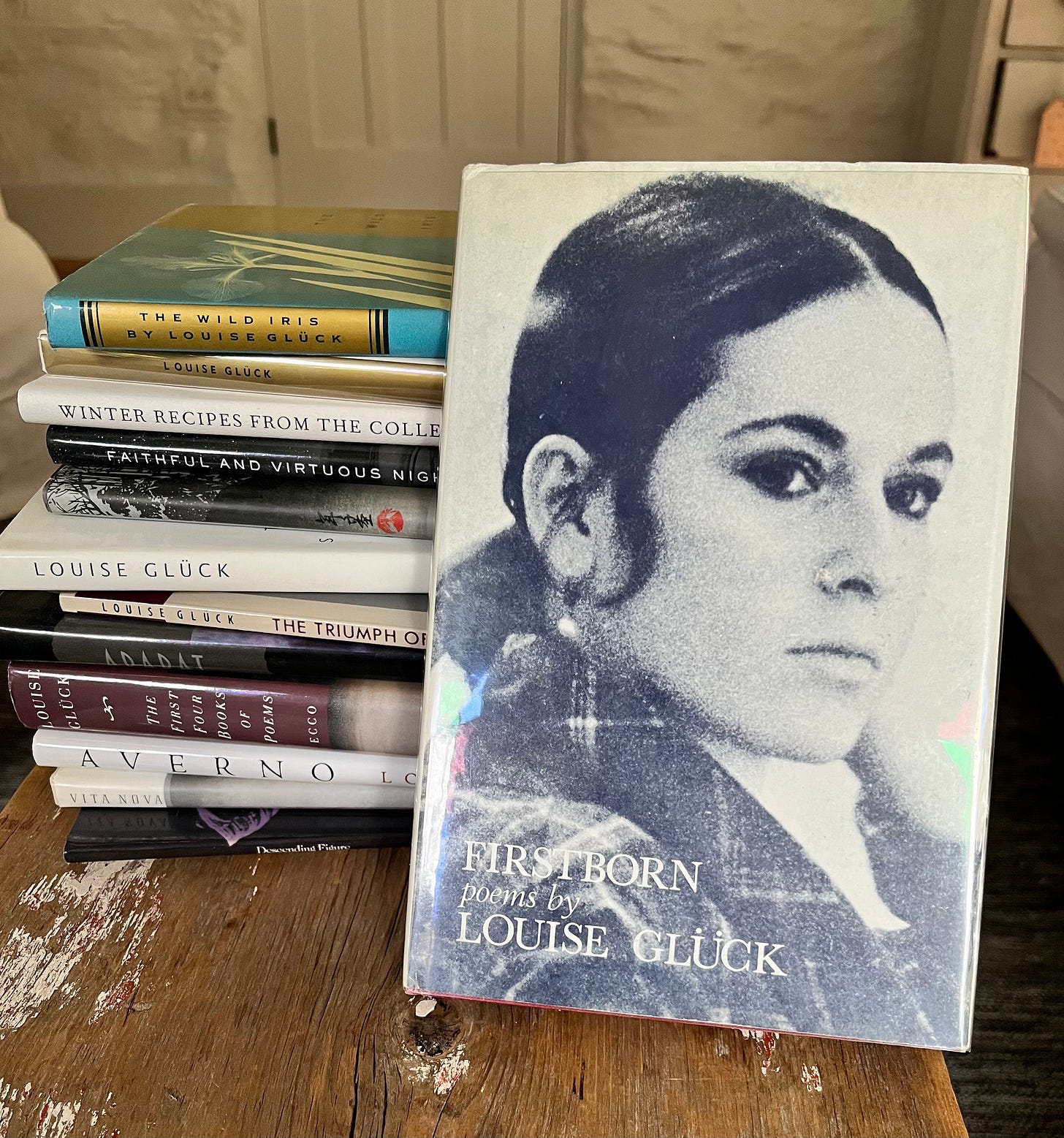

Louise Glück’s death yesterday sent me to my bookshelf where I took down all of her books. I made a fire in the stove, and in my chair with a stack of her books next to me, I spent the evening reading her poems. The spell these poems cast is something the best poems achieve: they collapse time, they assign language to that which is ineffable, they present the interior life as speech acts capable of achieving intimacy with strangers. They also build within the reader a kind of room—one can live in and move through.

They collapse time. That’s exactly it. Thank you.

Thank you, Mark, I so appreciate this telling tribute.